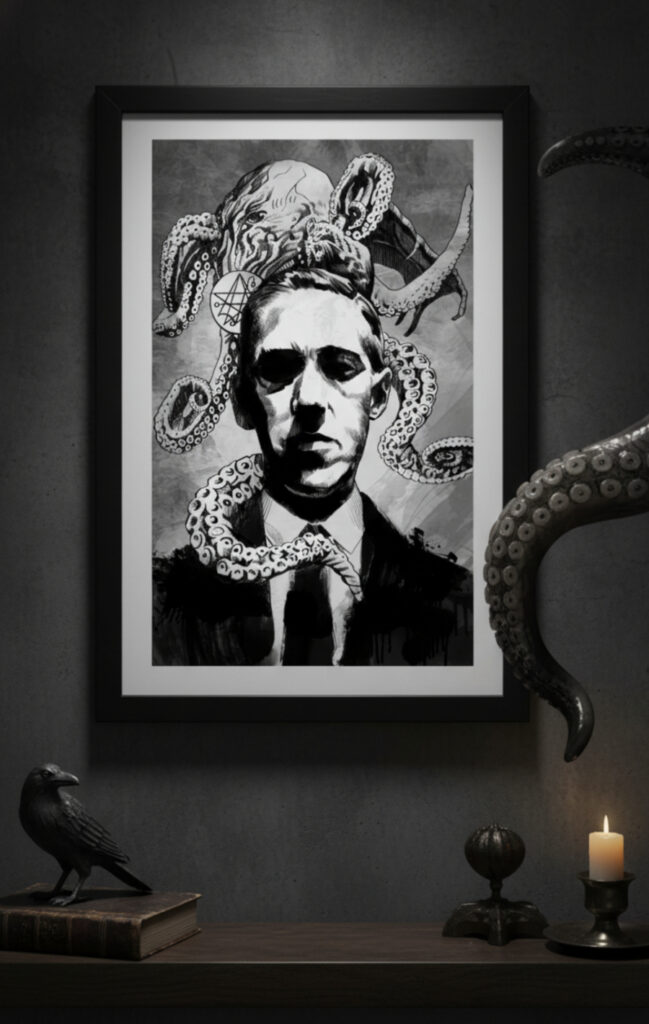

10 Eerie Truths About H.P. Lovecraft and His Mythos

“The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.”

From the cosmic horrors of Cthulhu to the creeping madness of The Shadow Over Innsmouth, H.P. Lovecraft built a universe that still shapes horror fiction today. This art piece captures the eerie wonder and intellectual dread at the heart of his mythos — a tribute to the dreamer who looked into infinity and saw monsters staring back.

ARTIST, ILLUSTRATOR WRITER

Disclaimer: In the article below there are links to several of Edgar Allan Poe’s books. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Lovecraft wrote his first horror story at age six.

As a child in Providence, Rhode Island, H.P. Lovecraft was plagued by vivid night terrors — visions of faceless beings, towering creatures, and dark corridors that seemed to stretch forever. Instead of fleeing from his fears, he began to explore them through writing. By the time he was six, Lovecraft had written stories inspired by The Arabian Nights — a spark that would one day lead to masterpieces like The Colour Out of Space and The Dunwich Horror.

Those nightmares would become the foundation for his later works, where human frailty meets incomprehensible cosmic forces. In his mind, horror wasn’t about ghosts or blood — it was about the unsettling realization that humanity is insignificant in a vast, indifferent universe.

He was a self-taught scholar.

He didn’t name the “Cthulhu Mythos” — others did.

If Lovecraft’s strange imagination calls to you, you’ll be drawn to the eerie beauty of my limited-edition art print — available here.

He was almost unknown during his lifetime.

Despite being one of the most influential writers in modern horror, Lovecraft never achieved fame while alive. His stories appeared mainly in pulp magazines like Weird Tales, earning him a few dollars per publication. He lived frugally, sometimes skipping meals to afford postage for the hundreds of letters he wrote to fellow writers and fans. Ironically, those letters became crucial to his posthumous fame. Through them, he mentored and inspired other writers who later preserved and published his work. Lovecraft’s success, like the beings he imagined, came long after he’d vanished from this world.

Lovecraft’s nightmares shaped his geography.

He hated the idea of “happy endings.”

In Lovecraft’s worldview, human optimism was almost delusional. His stories rarely ended well — not because he sought to shock, but because he saw cosmic despair as the truest form of realism. To him, the universe was vast, cold, and indifferent to human existence.

This philosophy, sometimes called cosmic pessimism, gave birth to a new kind of horror — one where the scariest revelation wasn’t death, but meaninglessness. His characters didn’t simply die; they went mad from realizing how small and powerless they truly were.

Lovecraft was fascinated by dreams.

Lovecraft claimed that many of his tales were inspired directly by his dreams — vivid, recurring sequences filled with alien cities, ancient gods, and strange dimensions. He kept meticulous notes of his “night-visions,” often waking in the middle of the night to record details before they vanished.

Those dreams formed the backbone of his “Dream Cycle,” which includes The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath and The Silver Key, reveals how deeply his subconscious fueled his storytelling. They blur the line between fantasy and nightmare, suggesting that Lovecraft’s greatest gift was not invention, but translation — bringing the subconscious to life on the page.

His influence stretches across every medium.

Though he died in obscurity, Lovecraft’s reach now extends into nearly every form of media. His ideas have shaped films like The Thing and Event Horizon, video games like Bloodborne and Eternal Darkness, and the works of authors such as Stephen King, Neil Gaiman, and Guillermo del Toro.

Even psychology and philosophy have borrowed from him — the “Lovecraftian” idea of cosmic fear now describes the dread of the incomprehensible. His stories didn’t just change horror; they changed how we think about existence itself.

he Necronomicon never existed — but people still look for it.

One of Lovecraft’s greatest tricks was creating fiction so convincing it blurred into reality. The Necronomicon, his infamous book of forbidden knowledge, was entirely his invention — yet countless readers have searched libraries and occult shops for copies ever since.

He even wrote mock histories of the book, naming its fictional author (Abdul Alhazred) and tracing translations across centuries. Today, fake editions of the Necronomicon still circulate, proving that Lovecraft’s most enduring magic was making people believe in impossible things.

His legacy is both brilliant and complicated.

Lovecraft’s imagination reshaped literature, but his personal views were far darker. His early letters contain racist and xenophobic ideas that many readers still grapple with today. Acknowledging his genius means also confronting those flaws — understanding the man without excusing the mindset.

Modern fans and creators have worked to reinterpret his mythos through a more inclusive lens, transforming cosmic horror into something richer, more human, and self-aware. In a way, even Lovecraft’s darkness continues to evolve — a fitting legacy for a man obsessed with the unknown.

His legacy is both brilliant and complicated.

Celebrate the Unknown

Step into the cosmic darkness with your own tribute to the Dreamer of Providence .